SPIRIT OF THE HARVEST – FULL TALK SCRIPT

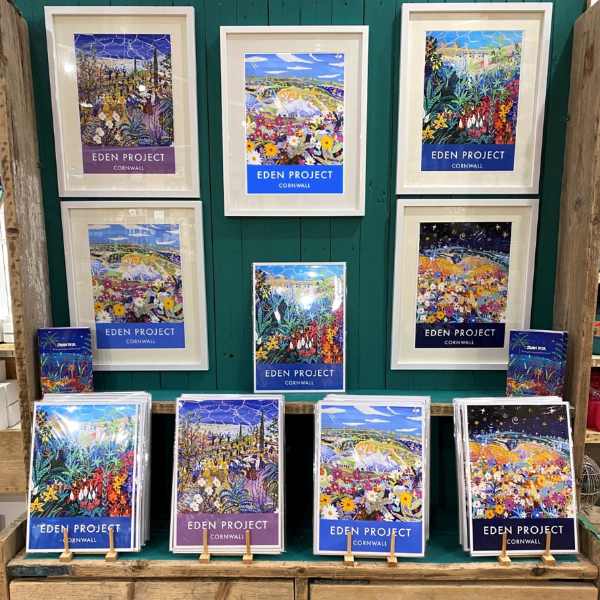

John Dyer

Eden Project – December Event

Thank you, Andy… (CEO Eden Project)

Good evening everyone.

It really is wonderful to be here with you at Eden tonight,

surrounded by these remarkable biomes,

in a place that has become so central to how we think about

plants, people, and the living world.

This evening I want to do three things.

First, to share how I fell in love with the extraordinary relationships

between plants and people —

what I call the spirit of the harvest.

Second, to take you with me on a short journey

through some of the harvests and plant-people stories I’ve painted around the world —

from grapes and bananas

to rice and potatoes.

And finally, to bring it back here,

to this exhibition,

to Eden’s mission,

and to why these stories matter so much

as Eden completes its first quarter century.

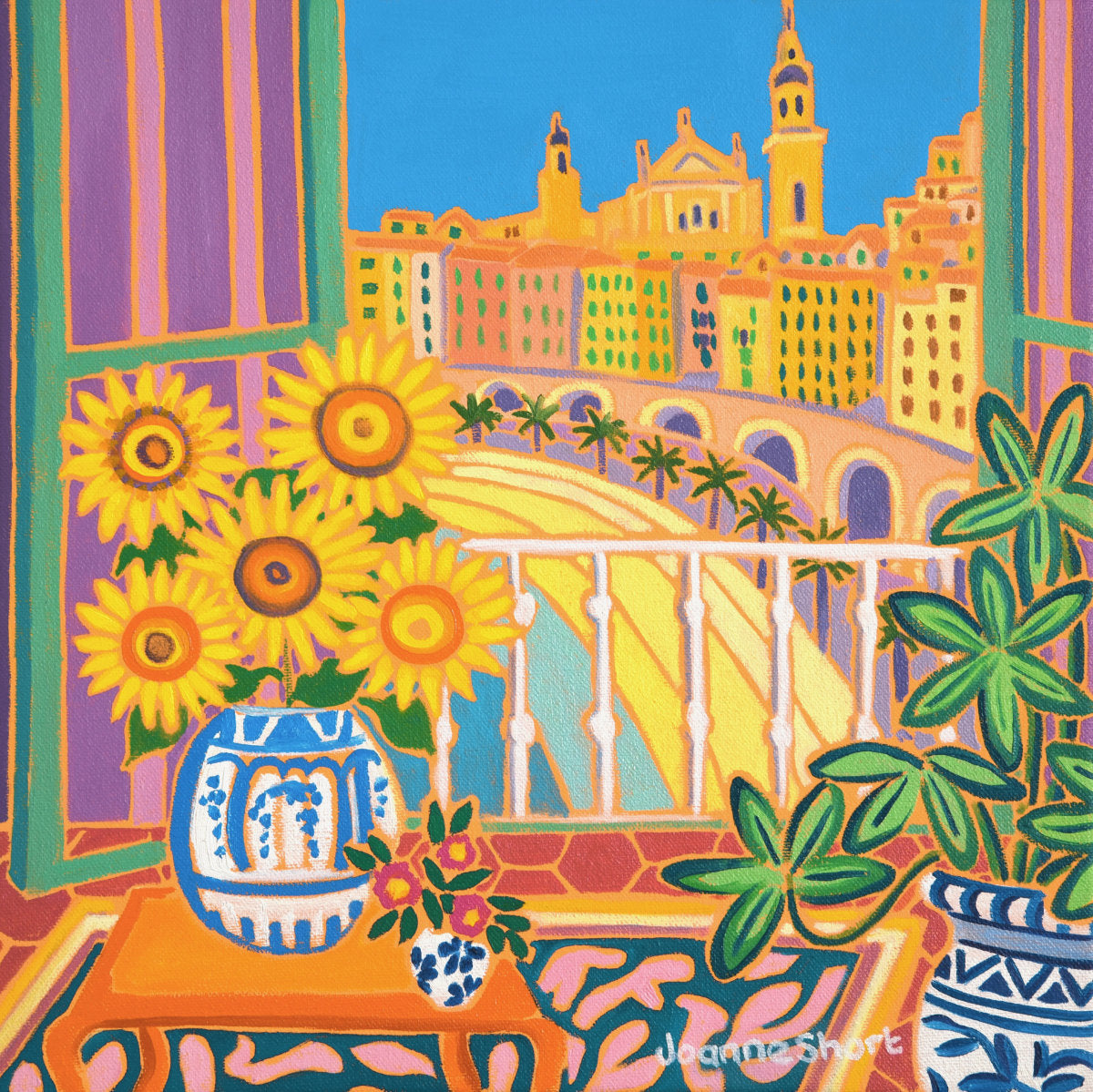

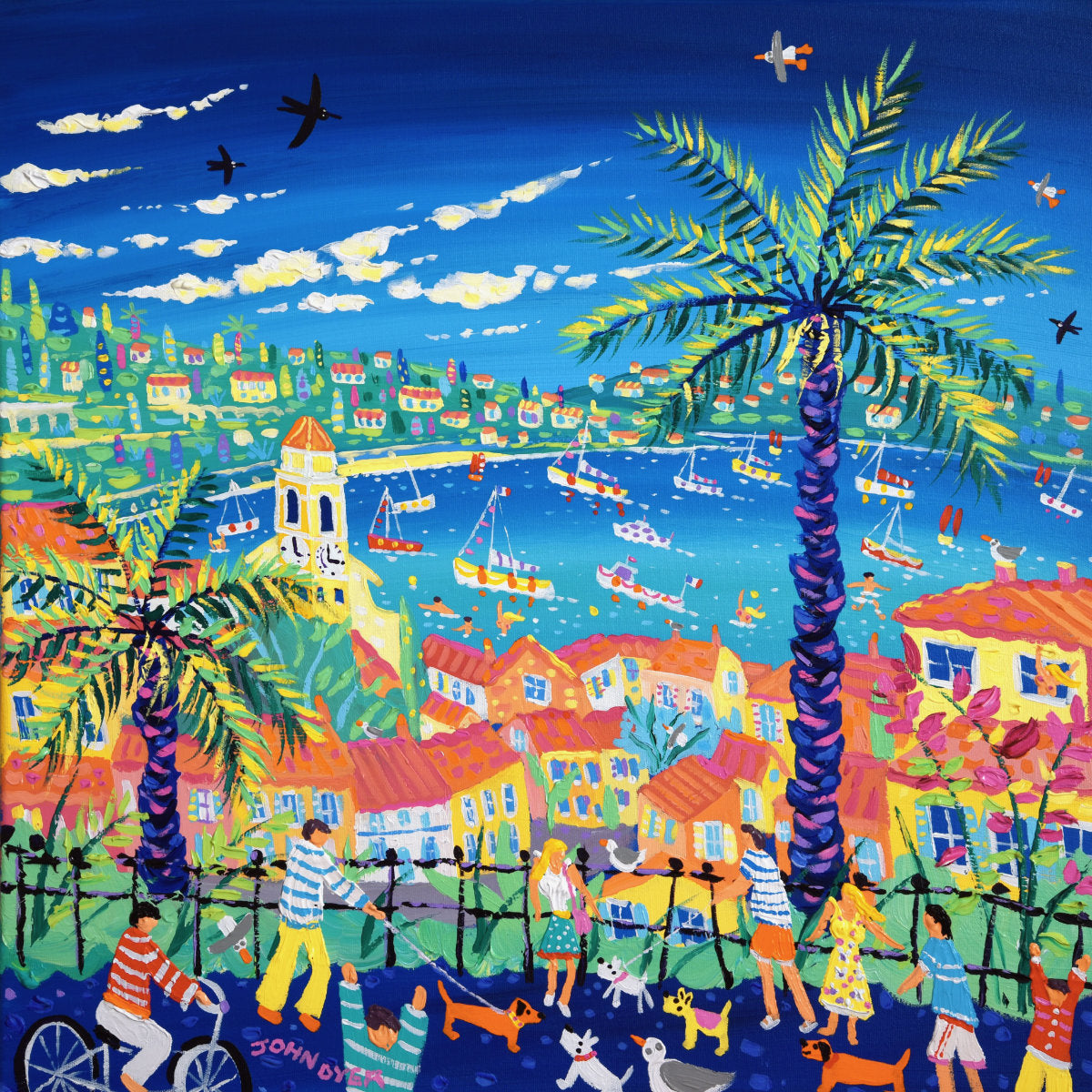

1. HOW IT BEGAN – PROVENCE TO EDEN

For me, it all began in 1997

on honeymoon in Provence with my wife and fellow artist, Jo.

We were there for sunshine, good food,

and the romance of it all,

but what captured my imagination

was the grape harvest!

The colour, the smell of crushed fruit in the heat,

the raw human spirit in the fields,

and the fragility of the whole thing —

the fact that a year’s work could be shaped

by weather, luck, or timing.

I realised that a harvest doesn’t just fill glasses and plates.

It shapes entire landscapes,

villages,

families,

and lives.

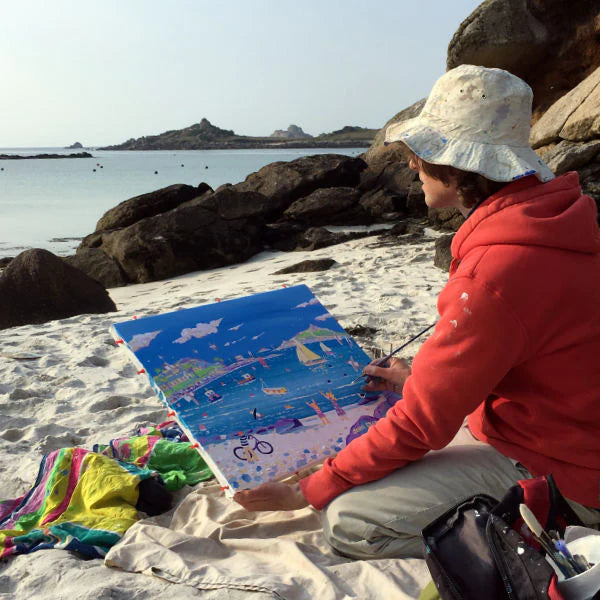

So I went back a year later with my paints,

determined to celebrate this connection

between people and the plants that sustain us.

A few years later, in the year 2000,

the Eden Project appeared on my radar whilst I was a lecturer at Falmouth School of Art

I became absolutely obsessed

with what was being planned here.

A brief conversation with Sue Hill from the Eden Project

somehow resulted in me becoming

their artist, or painter in residence

before the biomes had even opened.

I watched these extraordinary structures rise from the clay pit,

and at one point I asked Sue

whether Eden actually had any plants

I could paint.

Apparently, I was the only artist at that time

who had remembered to ask about the plants!

So once a week,

I made a pilgrimage from Falmouth

to Watering Lane Nursery,

painting among giant greenhouses

filled with young plants destined for Eden.

It was a living Noah’s ark of plants ready to colonise the biomes

And it was there

that I fell in love with the incredible diversity of plants,

and with the enthusiasm of Eden’s green team

who infected me — in the very best way! —

with their passion.

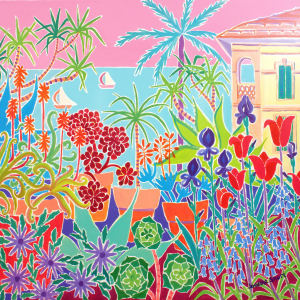

In 2002, Sue Hill asked whether I’d create a new series

of Mediterranean crop paintings for

World Food Day.

So off we went to Italy —

My wife Jo, our good friends David and Rose Ashe (who I think are here this evening)

Rose providing world-class photography of the mini-expedition and David world class picnics —

and we painted among vines, olives,

and landscapes steeped in centuries of harvest.

Those paintings set me on the path

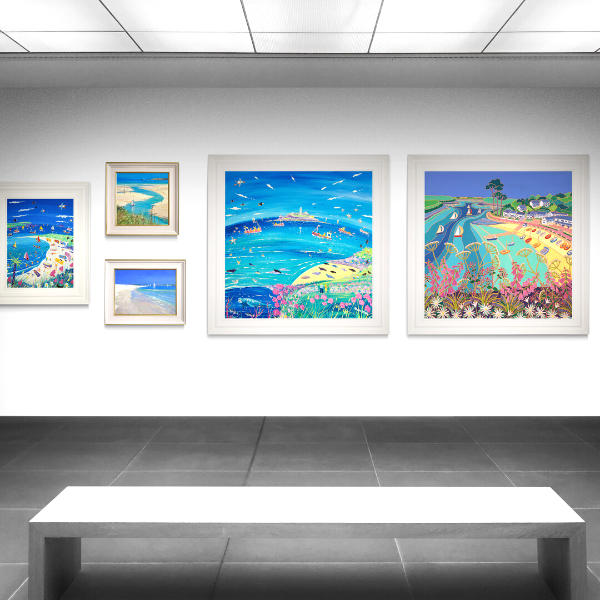

that you can see represented in this exhibition tonight —

including my new French paintings —

as they are all connected by this thread of plants and people.

That Italian harvest exhibition then led to a message

from an organisation with the rather brilliant name

INIBAP — the International Network for the Improvement of Banana and Plantain.

They asked if I would create a banana-inspired smallholder harvest painting

for their annual report.

They had a fee to pay me too, which is remarkable, as artists rarely get paid!

And, being an artist who is not used to being paid

I used the entire fee

to get to the Costa Rican rainforest

to paint that banana inspired painting.

I am very good at that sort of maths.

Never any profits!

And that takes us

to the first big harvest story.

2. COSTA RICA – BANANAS, CACAO AND APPLE SHIRTS

So — in 2003, off I went to Costa Rica.

I needed someone to carry bags and capture a few photographs,

so my friend David volunteered.

Some of you might remember him as the picnic man from Italy.

Now, David worked for Apple computers,

and he took full responsibility for his own wardrobe.

I packed sensible expedition clothes.

David packed a selection of crisp white Apple cotton shirts.

Perfect, he thought,

for the rainforest.

We arrived with paints, canvas,

Apple shirts,

and — for reasons still unclear —

a large Delsey suitcase whose little wheels

absolutely refused to travel across a rainforest floor - oh why hadn’t I packed a rucksack!

David also had high expectations

of a rugged 4x4 vehicle

for our journey across the mountains and down the Caribbean coast to the Panama border

What we actually received

was a rather small and slightly odd Toyota Yaris

His face when he saw it

was something I wish I’d painted.

We set off up roads so rutted

that an articulated lorry nearly tipped over onto us

we actually jumped out of the Yaris at speed!

I explained —

as calmly as possible —

that the budget was a little tight to have a decent vehicle.

Each day I painted

smallholder plots of bananas intercropped with cacao:

a beautiful system,

the bananas shading the cacao,

the whole place humming with life.

And each day,

David and I quietly - expected to die!

Nobody had mentioned

that everyone wears wellington boots

to avoid snakebite

in the deep banana leaf litter.

We had neat white trainers.

At least my Rohan clothes held up.

David’s Apple shirts however

slowly disintegrated into a white heap of sweaty wet material

and when he got home

he never unpacked —

he simply put the whole suitcase on a bonfire!

The farmers found us wildly amusing I am sure—

a pale English painter

and an official-looking Apple representative

sweating gently beside him.

The rainforest wildlife was astonishing —

insects roughly the size of dinner plates —

and some of those extraordinary creatures

appear in the paintings next to the rainforest biome if you look carefully

Costa Rica taught me about biodiversity,

about the beauty and intelligence

of smallholder farming,

and about just how generous farmers can be

even when they suspect you’re completely mad!

And after that…

of course I wanted another adventure.

3. THE PHILIPPINES – RICE, DUST AND DUCKS

The next chapter was the Philippines,

for the 2004 United Nations International Year of Rice.

I was invited to IRRI,

the International Rice Research Institute,

located in Los Baños —

in a region that also happened to be

a stronghold of a guerrilla movement.

So it seemed like the ideal place

to paint rice!

My friend Tim Varlow, a BAFTA-winning video graphic designer from London —

and the very same person who first dared to explore the Amazon rainforest with me back in 1989,

when we managed to make our translator very ill with malaria and abandoned her in Manaus, survived three car accidents,

bartered cash on the black market, and were even threatened at gunpoint —

yes, that Tim,

who clearly has a terrible memory —

offered to carry my bags this time.

Outside of the IRRI campus in the Philippines

we always had two bodyguards —

and if they said “we’re leaving”,

we left.

No questions.

Just bundled into an official IRRI vehicle.

Meanwhile,

I was blissfully captivated

by the harvest itself:

the gathering of rice straw,

the winnowing of grain into the hot, dusty air,

workers wrapped in scarves and masks

against the intensity of the day and the backdrop of volcanoes

Tim, on the other hand,

became slightly restless

and wandered off to sketch

lone water buffalo

at extraordinarily close range.

These enormous animals stood there

considering all the efficient ways

they might remove him from the planet

with a single nudge.

One evening we slipped away from our bodyguards

and left the IRRI campus to explore the area on foot.

We walked down roads lined with ditches,

past barking dogs,

looking for “downtown” Los Baños.

Instead, we found pitch darkness,

rubbish heaps, barking vicious dogs

and a group of far-too-curious locals.

Nobody noticed Tim —

he blended in perfectly

with his scruffy beard and slight build.

I, however,

in my pale expeditionary long trousers, long sleeved shirt, and clean shaven pale face

looked like a lost British geography teacher.

In the end, to get us out of a fix, and away from the vividly imagined possibility of being taken as hostages by the local guerrilla army,

Tim did the obvious thing.

he hailed a passing motorcycle and sidecar.

We climbed in —

full Wallace and Gromit style —

with Tim fitting beautifully

and my head repeatedly hitting the roof.

We hit a speed bump at speed,

my head made one last major impact

and the roof politely detached itself.

We made a very rapid retreat

back to the IRRI gates on foot.

I was waved straight in.

Tim, now indistinguishable from a local,

was stopped by security

and I had to vouch for him.

The rice harvest offers countless details:

in some places the rice is dried on the road,

and cars, lorries and the brilliantly decorated jeepneys

drive over it all day.

So — do wash your rice.

Not all the grains are collected,

so after the harvest

families and farmers release thousands of ducks

into the fields

to hoover up the leftovers.

Children do the same,

picking up grains one by one

for another bowl of rice at home.

And at the weekends

those ducks become racing ducks

in towns full of cheering and betting.

It is culture, economy and ecology

woven together with extraordinary elegance.

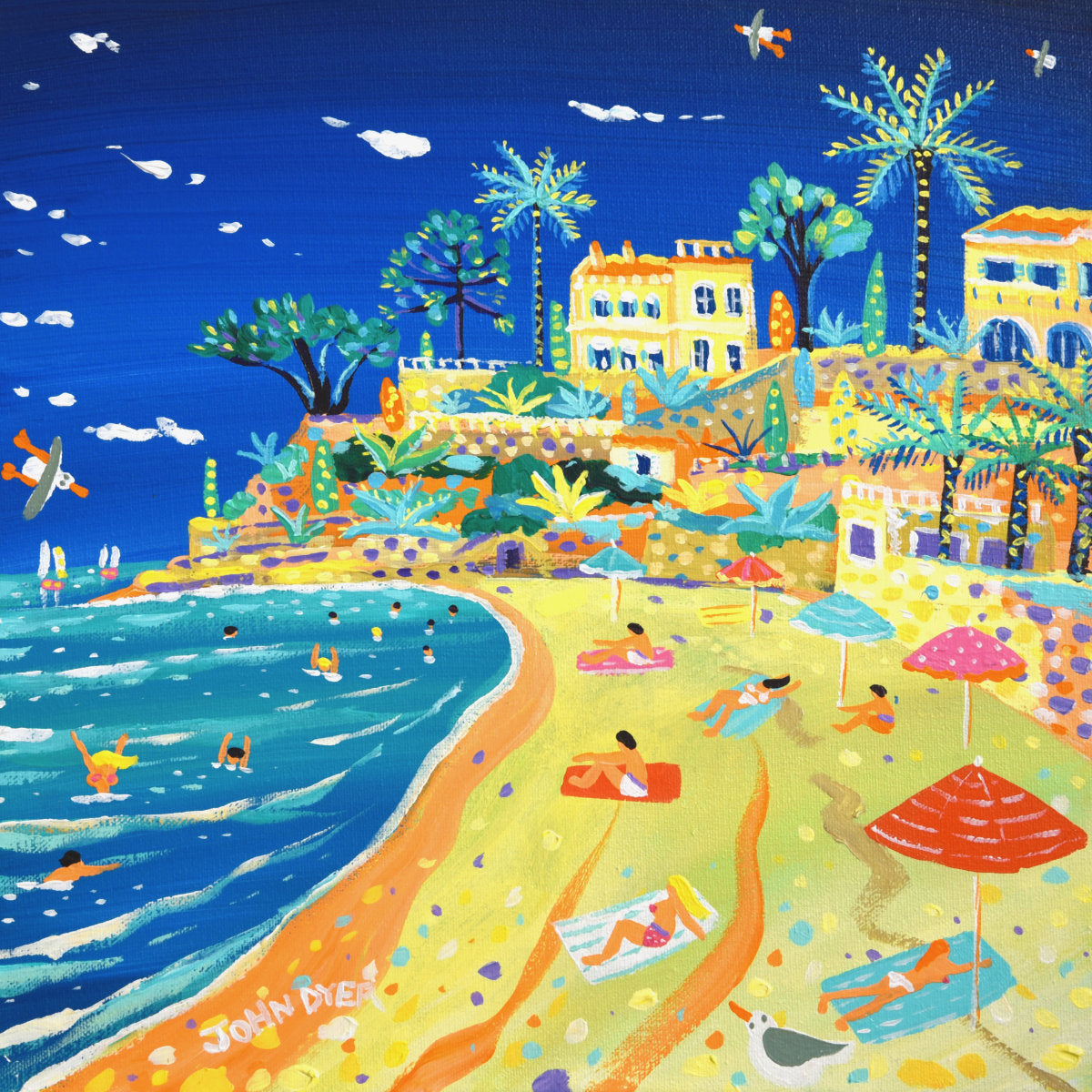

Rice is also grown and harvested in many countries,

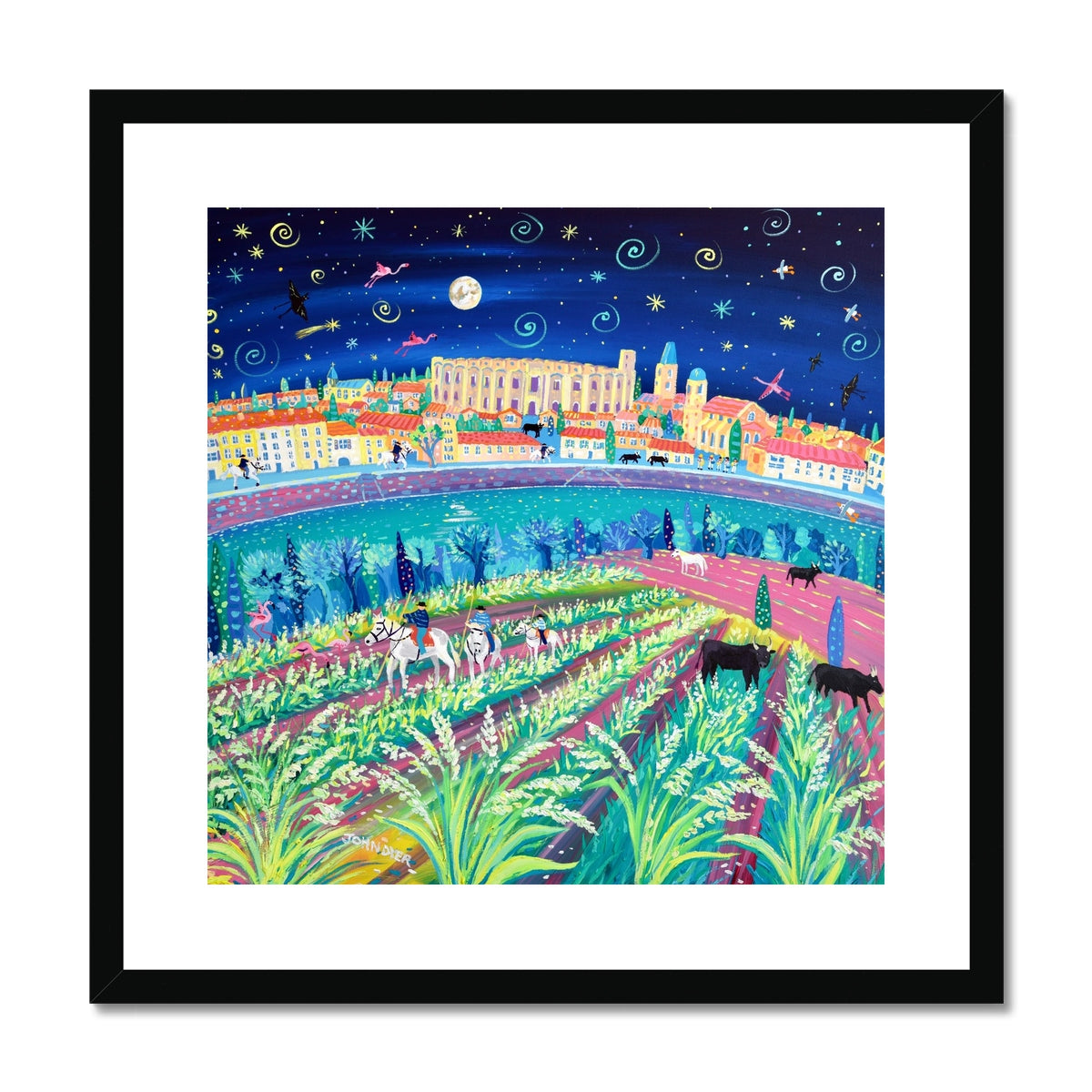

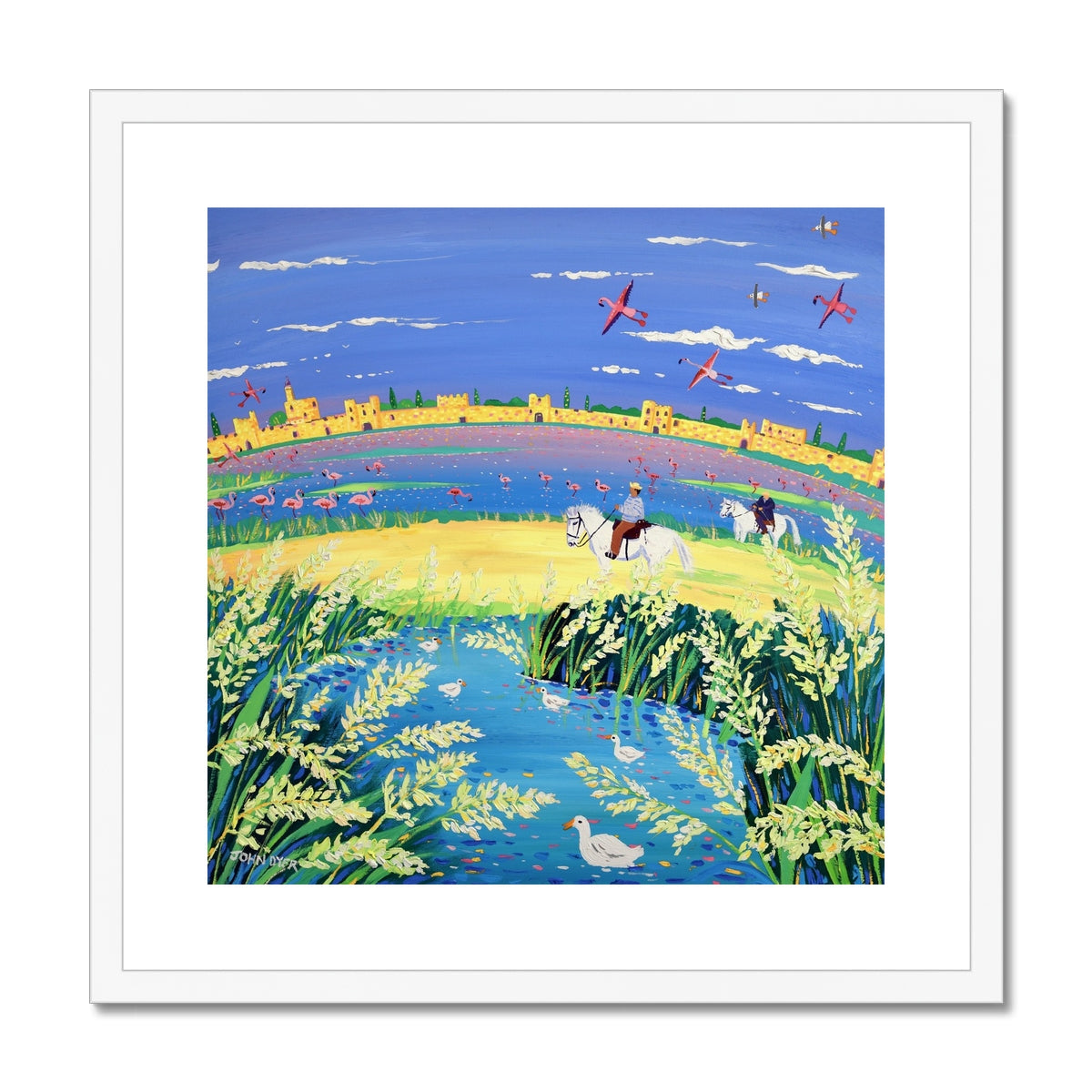

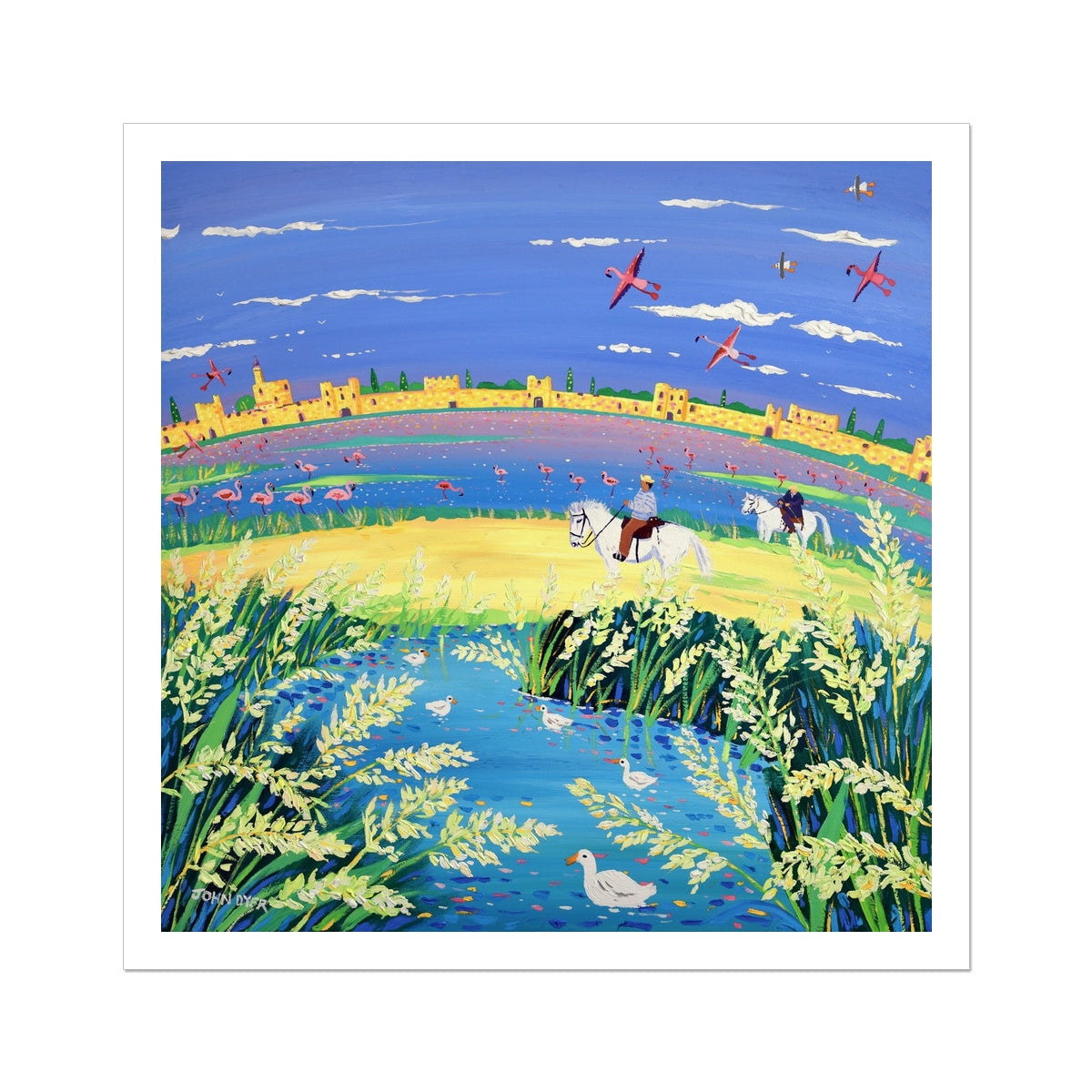

and close to home in Provence —

a landscape I love,

a place I lived for three years,

and one filled with fond memories of the grape harvest

and of my honeymoon with Jo.

With the Camargue’s white horses, black bulls

and flocks of flamingos,

it is another landscape shaped by a crop,

and one that even holds its own rice festival in Arles,

a place steeped in culture, colour

and centuries-old festivities.

And as for my mosquito stories from the Camargue,

well… those will have to wait for another day.

But I hope you will enjoy my two new French rice paintings in the link building just outside this biome

4. PERU – POTATOES, PACHAMAMA AND A NEARLY ADOPTED CHILD

During our years living in the south of France

in 2009 another invitation arrived —

this time from CIP,

the International Potato Centre in Lima, Peru,

for the United Nations Year of the Potato.

The idea of flying to the Andes to paint potatoes

seemed laughable to our French friends,

but I was captivated.

Having realised that bag carriers

tend to come with questionable clothing

and transport choices,

I travelled to Peru alone.

Languages have never been my strong point.

I have an A-star in doing them terribly.

I proved this in France

by accidentally informing the police

that twelve people were on fire in my Land Rover,

when I had simply meant to report

that my headlights had failed on the motorway

In preparation for Peru I brushed up on some Spanish

only to arrive in a village at 4,500 metres (nearly 15,000 feet up or about 2.8 miles high,

where everyone only spoke the Inca language Cuzco Quechua

There I was,

far up in the Andes,

with very little oxygen,

and absolutely no shared vocabulary.

I was handed a scythe

and immediately put to work

harvesting broad beans as dusk fell in what must be one of the remotest villages in the Andes.

I smiled,

laughed in the wrong places,

and befriended a silent, slightly judgemental donkey.

Afterwards,

my painting bag — now with rucksack straps

because I do sometimes learn things —

was lifted and carried off

through narrow mud paths

to meet my host family.

We shook hands and smiled a lot.

Temperatures plummeted

and I did begin to wonder

where my bed might be.

Then a group of people arrived,

my bag moved again,

and it became clear

that there had been some sort of dispute

about who should host the visiting artist.

At what felt like midnight

I was being led through utter darkness

to another mud brick house.

Note to self:

always pack an expedition torch.

My eventual bed

was above the cattle,

with a window with no glass,

a little plastic pot as a bathroom,

and thick llama blankets.

Buy the next morning I was a block of ice but

the Andes revealed themselves

in an electric, iridescent light.

My host family were wonderful.

The father led me for two hours up the mountains

to find a potato harvest in progress.

He strolled

I puffed.

He carried the canvas.

I carried my bag.

The harvest was magical —

tubers in every colour

lifted from the soil

onto bright Peruvian rugs

Women in bowler hats spinning wool

as they walked the paths.

Two pigs wandering through the landscape gently the rearranging the potatoes for me and creating a lot of animated people rushing after them

These are the things that enter my work —

not just scenery,

but life - I capture the narrative.

In the evenings I painted inside the house

by the light of the open cooking fire,

with two children watching every brushstroke.

My language consisted mainly of smiles and pointing,

which worked remarkably well

until I admired a particularly cute guinea pig.

They kept them in a guinea pig condominium

and during the day they roamed freely,

tidying up scraps of food from the earth floor.

I pointed and smiled at an especially handsome ginger and white one.

The family were delighted

and immediately carried it into the kitchen.

I am vegetarian.

There followed a burst of frantic facial signals

which were thankfully understood

and the guinea pig was returned unharmed to live another day in the condo.

Later, on Taquile Island,

I was invited to join a ritual to bless Pachamama,

Mother Earth —

involving shared beer

and the straightest line of beer

thrown across the soil you can manage.

Apparently my line was acceptable

because the farmer was delighted

and then presented his youngest daughter

in beautiful traditional dress.

He then offered me a pair of scissors!

At that very moment

my guide leaned in and whispered:

“Do not, under any circumstances, cut that child’s hair.

If you do, the family will expect you to adopt her

and pay for her childhood.”

We resolved it diplomatically

with more coca leaves - the local currency for cooperation,

I left without accidentally adopting a Peruvian child, which I am sure Jo is very thankful for.

What stays with me from Peru

is the wisdom in their biodiversity.

Farmers may plant dozens of potato varieties in one field

so that whatever the climate does,

something will survive.

It is resilience,

written into the landscape.

5. WHAT IT ALL MEANS

These journeys,

from Provence to Costa Rica,

from the Philippines to Peru,

have shown me again and again

how deeply plants and people

are intertwined.

There are over a thousand species of bananas and plantains,

yet we rely almost entirely on the Cavendish —

a single variety now vulnerable to disease.

High in the Andes there are more than four thousand potato varieties —

blue potatoes, orange potatoes, long ones, tiny ones —

often planted together in one field

so that whatever the climate does,

something will survive, there will be food.

And at IRRI they have worked with over one hundred thousand rice varieties,

breeding grains that can withstand - storms, flooding and drought,

and that have helped to feed countless millions of people.

Without biodiversity in our plants and crops

we are less able to withstand climate change.

Without biodiversity in our farming

we risk losing the insects, birds and animals

that bring our landscapes to life and sustain the web of life.

If we fail to protect and connect with Indigenous and tribal peoples

and learn from them,

we choose ignorance

at precisely the moment

we most need wisdom.

And if we forget

that we all live in one vast, interconnected biome called planet Earth

with so much we share as human beings

and differences that enrich us and that deserve to be celebrated —

then we lose sight of the best of ourselves.

And without art, literature and music

to celebrate our world,

to remind us of its wonder

and to show us what we stand to protect and lose

we risk becoming blind and deaf to its beauty.

And without hope,

we lose the very thing that carries us forward.

So, I hope my ethnobotanical paintings

will fill you with

joy,

colour,

and with love,

and with a warm optimism for our future

a sense that through

knowledge,

connection,

creativity

and the work of places like Eden,

we truly can shape a better world together.

Because with the calibre of people here at Eden

this world-class destination

doing such important work

to educate and inspire —

I truly believe

we can all leave here tonight

knowing we are adapting and building a better future for us all.

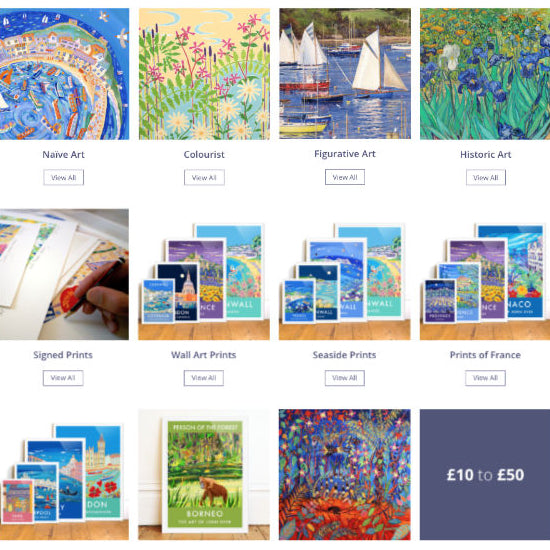

In a moment

I would love you to take your time to view

the paintings in here that are perfectly set in the Mediterranean biome

and the main ‘Spirit of the Harvest’ exhibition along the link corridor.

Scan the QR codes on the paintings in the link building

to read more of the stories behind them.

Enjoy the extraordinary biomes

and look at the plants with fresh eyes

knowing we have a deep connection to them.

And please do come and talk to me —

I’m very happy to answer questions

about my art,

the expeditions,

or indeed guinea pigs and how to avoid getting them cooked!

7. THANK YOU

I would like to thank the entire Eden Project team

for their hard work

and generosity in bringing this exhibition to life,

and for the visionary leadership

support and trust

of Eden’s Chief Executive,

Andy Jasper.

And to all of you,

a very happy Christmas,

and my heartfelt thanks for being here this evening —

for taking the time to see my paintings and to view the world through my eyes,

to celebrate our natural world

and our connection to it,

and for supporting the Eden Project

as it begins it’s next amazing 25 years.

Thank you.